Democracy and decency: a policy push to tackle online harms

Image: Sébastien Thibault

Democracy and decency: a policy push to tackle online harms

Image: Sébastien Thibault

How do you curb the toxic flow of hate speech, harassment, and false information on online platforms that many fear is undermining the health of our democracies? That’s one of the timely questions examined at the Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy at McGill’s Max Bell School of Public Policy.

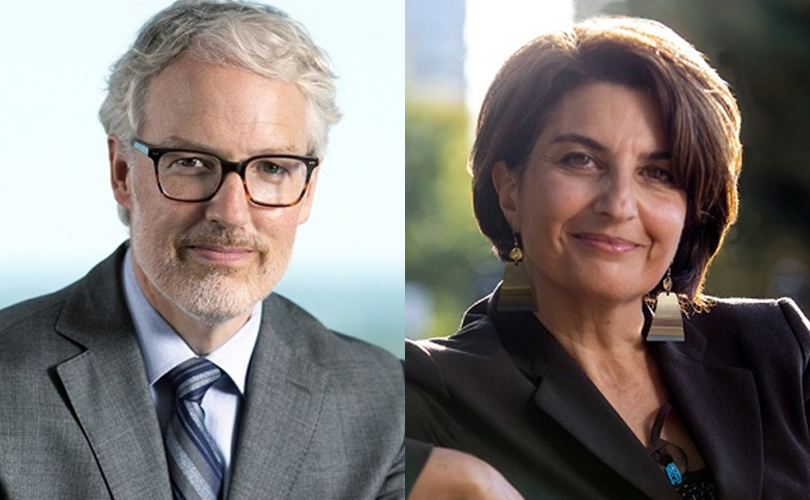

Taylor Owen, the Centre’s founding director and associate professor at the Max Bell School, has long sounded the alarm about online harms and advocated for change. Public attitudes began to shift in recent years, he says, and picked up steam during the pandemic.

“When people saw their kids go online for two full years, and what it did to them, it really sped up this concern that we’re not taking the impact of these technologies seriously enough,” says Owen, Beaverbrook Chair in Media, Ethics and Communications.

Owen has played a prominent role in informing the debate in Canada about the governance of online platforms, including big social media companies. He’s part of an expert advisory group that’s providing advice to the federal government on a regulatory framework to tackle harmful content online. Canada is expected to introduce an online harms bill in 2023.

The nature of these platforms is so pervasive – they touch so many aspects of our lives – that to leave them ungoverned and to leave them to the whims of the market feels reckless to me.”

Taylor Owen

He also leads the Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy at the Max Bell School, which conducts critical research and policy advocacy about the changing relationship between media and democracy – and encourages the development of public policy that minimizes systemic harms embedded in the design and use of emerging technologies.

Social media platforms have been largely ungoverned to date, says Owen, who contends the case for regulation is now clear.

“The nature of these platforms is so pervasive – they touch so many aspects of our lives – that to leave them ungoverned and to leave them to the whims of the market feels reckless to me and really puts at risk some core aspects of our society. Yes, our elections, but also all the other ways in which our society is mediated by these technologies.”

Much of our online activity is determined by market forces of a few American companies, adds Owen, who mentions Twitter as an example. “If we expect the interests and whims and politics of one billionaire to shape a critical piece of our infrastructure and how we communicate with each other in our society, there’s a real risk there.”

Bringing research and policy conversations into the public sphere

The Centre actively communicates its cutting-edge research as well as that of scholars from around the world, to the public and policymakers. Many of its public engagement activities in 2022 explored mitigating online harms: in op-eds, on Owen’s “Big Tech” and “Screen Time” podcasts and at the Centre’s annual Beaverbrook Lecture, which featured Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen and Jameel Jaffer, Director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. (Haugen joined the Centre in spring 2023 as Senior-Fellow-in-Residence.)

That same day, the Centre kicked off its Global Governance of Online Harms Conference that was “wildly successful”, notes Sonja Solomun, the Centre’s deputy director. In one session, students heard from Haugen, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate and journalist Maria Ressa who stressed: “If you don’t have facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust.”

“We do a lot of direct public outreach on the policy areas that we think are affecting Canadians daily,” says Solomun, a PhD candidate at McGill who leads the Centre’s Climate Justice, AI and Technology Program.

Supriya Dwivedi, BSc’08, the Centre’s director of policy & engagement, brings the Centre’s expertise and research to the public conversation.

“Often a lot of these conversations tend to happen in silos – between academics and experts in one silo, and then you’ve got government and the public talking in this other silo. What we’re really trying to do is to break that down so that they’re talking and communicating to one another.”

We’ve got a real opportunity here for Canada to be able to really lead the way and learn from what other jurisdictions have done, and to incorporate that into our own online governance framework to ensure that we’ve got the best digital policy worldwide.”

Supriya Dwivedi

A case in point: When Haugen was in Montreal for the Centre’s events, Dwivedi assumed government officials would want to hear from the responsible tech advocate and put out feelers. Haugen ended up meeting with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, BA’94, and his chief of staff, as well as with a number of ministers from Trudeau’s cabinet.

A lawyer by training with a media background, Dwivedi hosts the Centre’s Digital Policy Rounds webcast, a collaboration with four other policy-oriented research centres, and writes columns and op-eds, including about the need to address online harms.

“The UK and the EU have been immersed in these conversations for quite some time,” Dwivedi says. “It’s imperative that we catch up, because we’ve got a real opportunity here for Canada to be able to really lead the way and learn from what other jurisdictions have done, and to incorporate that into our own online governance framework to ensure that we’ve got the best digital policy worldwide.”

Generous support propels research and engagement

A lot of the Centre’s work doesn’t fit within conventional academic models, which is why donor funding is so crucial, according to Owen.

“It enables us to do what we do,” says Owen. Funding for traditional academic work – which the Centre also receives – isn’t “purpose-built for the kind of work that we think is essential in this debate right now,” he says of activities such as public engagement.

The Beaverbrook Chair and Lecture are funded by the Beaverbrook Foundation. The Centre’s projects also receive philanthropic support from Reset, Luminate, The Rossy Foundation, and the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation.

Many private foundations are now concerned about the integrity of our democracy and the role of information flows in the media, Owen says. “Their ability to boost research and engagement into exactly this problem fulfills their mandate, but also allows us to do our work. We couldn’t do it without them.”

For the past three years, the Centre’s Media Ecosystem Observatory has examined how misinformation and disinformation impact citizens’ attitudes and behaviours and the overall strength of our democracy. Owen says false information doesn’t matter if it’s not influencing us. But it does if it’s negatively changing our behaviour: for example, by making us undermine the credibility of institutions or convincing us not to get vaccinated or dividing us against each other. “So, understanding the role information plays in our democratic society is critical.”

The Observatory studied the 2019 and 2021 Canadian federal elections as well as the 2022 Quebec provincial election and observed a similar dynamic. False information doesn’t necessarily change the results of elections, Owen says, but it is doing two things: It’s leading to people’s declining trust in democratic institutions and the media, and increasing polarization.

“It’s making us not just more divided but disliking people of other political persuasions more. Both of those trends I think are really worrying, and we see it across the board. We also see it in the COVID work we’ve done.”

The Observatory is poised to grow substantially this year, buoyed by a $5.5 million grant in federal research funding.

We’re not going to get rid of hateful speech, but we can minimize how many people see it. We can minimize the financial gain for people spreading it. And, ultimately, we can minimize the harm it does to the individuals it is directed at and to society as a whole.”

Taylor Owen

A duty to act responsibly

For a long time, there has been a tendency to blame the problems of the internet on individuals, Owen says. The Centre takes the approach that the bad actors are incentivized and made worse by the design of social media platforms: their content can go viral, negative content is promoted above positive content, hate speech over more moderate content.

“That’s what we need to target with policy,” Owen says. “We’re not going to get rid of hateful speech, but we can minimize how many people see it. We can minimize the financial gain for people spreading it. And, ultimately, we can minimize the harm it does to the individuals it is directed at and to society as a whole.”

Balancing platform governance with freedom of expression is difficult, acknowledges Owen, who believes the upcoming Canadian legislation strikes the right balance. “Getting the policy right matters because we’re going to have a lot of fights in Canada about whether this impacts speech or not. But by focussing on the design and incentives of the system rather than the individual acts of speech we sidestep many of these concerns.”

Both the Canadian Commission on Democratic Expression and the federal government’s expert advisory panel advocated for a duty to act responsibly, which would oblige online platforms to design their systems in a way that minimizes harm.

In the academic world, the final step of actively engaging with the policymaking process often doesn’t happen, Owen says. One of the goals of the Centre is to do just that.

“To not just recommend a policy,” says Owen, “but to engage actively in the design, advocacy and implementation of public policy in this domain to ensure it’s reflecting what we know in the research world, as opposed to just hoping they adopt our ideas.”